June 16, 2023

Stories from China (Part 33)

By Simon J. Lau

I visited Leifeng Pagoda, originally built in 975 during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. This was a time of intense political upheaval in China, with dynasties rising and falling in rapid succession. According to legend, King Qian Chu of Wuyue had the pagoda constructed for his favorite concubine, Huang Fei, to celebrate the birth of his son. This is why it’s still known locally as the “Huang Fei Pagoda.” Despite the chaos of the era, the pagoda endured and eventually became one of Hangzhou’s most iconic landmarks.

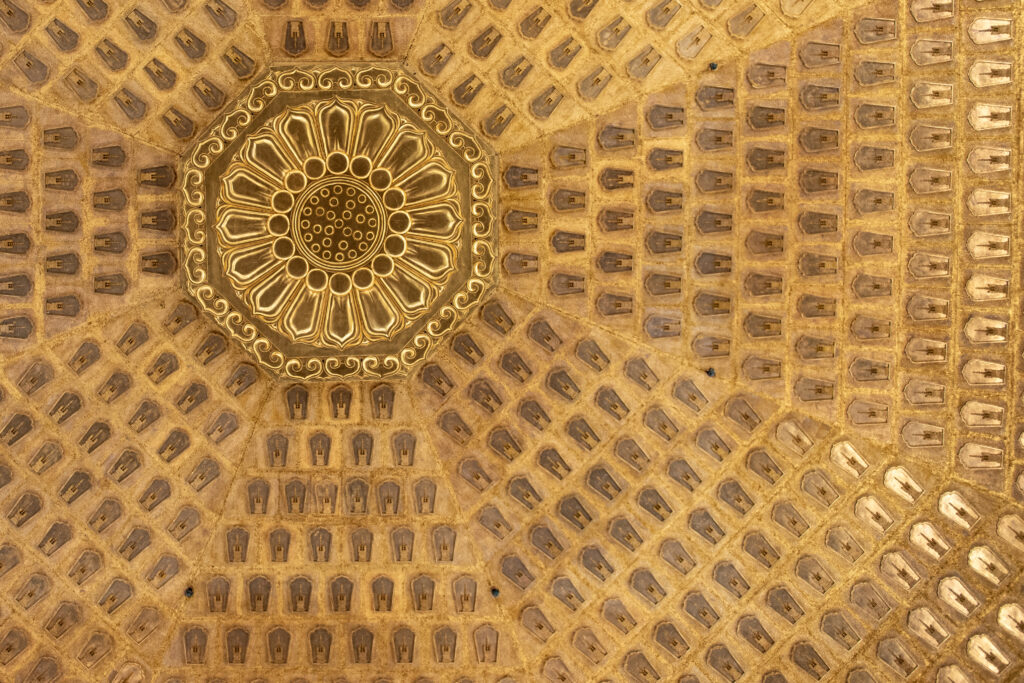

Inside the modern structure, which was rebuilt and opened in 2002 to replace the original Leifeng Pagoda (which collapsed in 1924), the ceiling is stunning. Intricate golden patterns radiate outward, each small detail carefully crafted to catch the light.

Below the main hall lies the preserved foundation of the original pagoda. The excavated area reveals crumbling brickwork, leaning walls, and piles of stone, all left in place to show the building’s ancient footprint.

In the afternoon, I tried beggar’s chicken, a famous Hangzhou specialty. The dish involves marinating a whole chicken, stuffing it with spices and fillings, then wrapping it in lotus leaves and a thick layer of clay before slow-roasting it. When it’s ready, the clay shell is cracked open to reveal tender, fragrant meat inside. The recipe is popular throughout China, with many regions claiming it as their own, but most agree that it originated here in Hangzhou.

I honestly didn’t think I could finish the entire thing when I ordered it. It looked enormous, but this was one of those rare times when my appetite proved bigger than my expectations. I ate everything: head, feet, body, and all! By the end, I was so satisfied and so full that I decided the only appropriate way to celebrate my triumph was with a long afternoon nap.

Finally, I returned to the burger bar from yesterday, Black Hole Elixir. I struck up a conversation with two graduate engineering students seated next to me. They had overheard me talking about my travels and wanted to learn more. Both were students at Zhejiang University, one of the top universities in China, and I made sure to heap plenty of praise on them.

The Chinese place a lot of importance on university rankings, and being admitted to a top school is considered one of life’s major achievements. Yet despite their academic success, both students were worried about their job prospects after graduation. China’s economy has slowed substantially over the past decade, and COVID only made things worse. On top of that, structural challenges such as ballooning government debt, an aging population, and weakening real estate and tech sectors have pushed youth unemployment, especially among college graduates, to its highest levels on record. There are no easy answers here.

After the grad students left, I spent time talking with my bartender again. She asked what I thought of China now that I’d been here for a while. I paused for a moment, then told her that my biggest surprise was the Chinese people’s strong desire for safety. For example, AI facial recognition systems are deployed explicitly in the name of public safety, whether for crime prevention, pandemic controls, or maintaining social stability. Likewise, the country’s high household savings rate reflects a desire for financial security.

This pursuit of safety runs deep. China’s long history is filled with periods of turmoil, from the era of warring states to foreign occupations to the political, social, and economic upheavals of the Mao years. These collective memories, many of them modern, have left a lasting imprint and created a deep cultural preference for safety and stability.

She seemed surprised that I found this so striking. I explained that in America, with its relatively short history and mostly stable existence, we simply don’t value stability in the same way. Above all else, we place the highest value on individual freedom. That’s why Chinese and Americans often can’t see eye to eye on many issues, especially social ones. Our different histories have shaped different priorities, and recognizing that helped us both understand why our perspectives sometimes feel worlds apart.

Comments are closed.