April 28, 2025

Letters from Indochina (Part 29)

By Simon J. Lau

Today, I set off on the Ha Giang Loop! To keep with the Vietnamese food theme, I present to you my riding partner: Bun Bo (short for bun bo hue, a Vietnamese noodle dish). Like Banh Mi, she’s another Honda XR150. I’ve grown to like these little underpowered dirt bikes — they’re simple, reliable, and perfect for trips like this.

When I picked her up, I asked my vendor about police checkpoints. These are essentially bogus setups used to shake down foreigners. It’s gotten worse this year after a new “decree” significantly increased traffic violation fines — creating even greater incentives for corrupt police to exploit tourists.

My vendor explained that fines inside Ha Giang City could range from 3M to 7M VND (about $115 to $270 USD). However, they offered a workaround: for 500K VND (about $20 USD), they would drive me and the bike 20 kilometers outside the city, where standard fines drop to 2M VND (about $77 USD). I agreed to the service — and I’m glad I did. We passed two checkpoints on the way out of the city.

My driver not only transported me and Bun Bo out of the city, he also helped me find a working ATM (not easy — I struck out at two this morning) and filled up my gas tank.

When we pulled into the gas station, I knew I had made the right call bailing from the tour group — it was overrun with hordes of tourists. I nearly threw up. 🤮 I couldn’t imagine riding like that. It looked like a total shitshow.

I should add, most tourists doing the Ha Giang Loop sign up for what’s called an “easy rider” — where you ride pillion on the back of a local guide’s motorbike instead of driving yourself. It’s a solid option if you don’t ride, but let’s be honest: there really ought to be a weight limit for passengers. Some riders were obese — and not to be cruel, but that matters when you’re two-up on an underpowered scooter navigating mountain switchbacks and slick, uneven roads. It puts extra strain on the bike, throws off balance and handling, and increases the risk of accidents. It’s not just uncomfortable — it’s unsafe.

These bikes aren’t built for that kind of load. They’re underpowered, often poorly maintained, and definitely not designed to haul that much weight up steep grades or around blind mountain curves. But this is Vietnam, where — unfortunately — safety tends to take a back seat to convenience, cost, and whatever keeps the itinerary moving.

Eventually, the driver dropped me off at some random spot along the road and told me I’d run into a checkpoint up ahead. Sure enough, about an hour later, I hit my first one. Even though I knew to expect it, it still pissed me off.

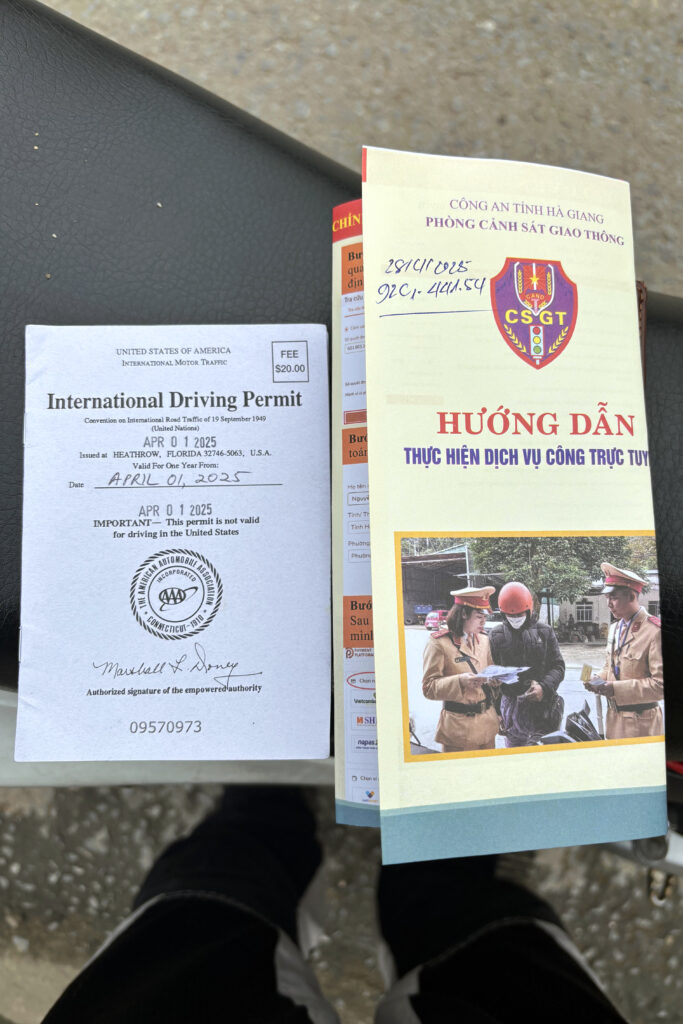

It went exactly how you’d expect a shakedown to happen: first, the cop explained why my documents were “invalid.” It’s not worth going into the excruciating details — it was all pretext anyway. Then he mentioned the official fine range (3M to 7M VND). But, lucky me — because this was a “minor infraction,” he was willing to settle for 2M VND if I paid cash on the spot.

I thanked him, handed over the 2M, and watched him slip it into his personal briefcase before giving me a slip of paper — supposedly my “fine receipt” — scribbled with my license plate and some made-up violation. After you pay this bribe, the police hand you a document like this that waives you from further stops along the loop. This was my first real encounter with brazen government corruption, and it left a bitter, bitter taste in my mouth.

Fortunately, I was able to enjoy the rest of the ride. I cruised through twisty mountain roads and stopped for lunch overlooking a wide valley filled with farmland, low houses, and limestone hills. It was exactly the kind of landscape I had imagined when planning this trip.

By afternoon, I reached Yen Minh, my final stop for the day. It’s a dusty town surrounded by low mountains, mostly used as an overnight stop for travelers. Right now, the main street is torn up for construction — they’re redoing the sidewalks and gutters, kicking up clouds of dust. With the sidewalks ripped out, all the pedestrian traffic spills into the street, making it even more chaotic.

Despite this, I was just happy to get off the saddle and walk around. What surprised me about Yen Minh was that, despite being rural, the town is packed with tube houses — tall, narrow buildings stacked tightly side by side. Residents have adopted this urban style of construction to signal success.

The houses are often only a few meters wide but stretch deep into the lot and rise several stories high. This design traces back to an old tax system where property taxes were based on the width of a building’s frontage, not its overall size. To minimize taxes, families built narrow but deep houses — a style that started in the north and eventually spread across the country.

The facades are usually the only part that gets much attention. Some are brightly painted or tiled, with elaborate balconies, detailed railings, and bold signage. The more successful the family, the more polished and elaborate the front tends to be. Although, I’ve looked inside many of these buildings. Once you get past the facade, the rest is usually plain and utilitarian.

Finally, my route from Ha Giang City to Yen Minh (about 62 miles, or 100 kilometers).

Comments are closed.