April 4, 2025

Letters from Indochina (Part 5)

By Simon J. Lau

Today started early with a full-day tour of Battambang’s countryside. Before hitting the road, I fueled up with a big plate of chicken and rice from a roadside spot near my hotel. It looked simple, but the food was fantastic. The chicken was tender and the rice was perfectly seasoned. Honestly, it blew yesterday’s upscale place out of the water.

This part of the world felt raw and unfamiliar, but in a good way. There were small farms with rice fields and livestock, winding dirt roads, and simple stilt houses tucked along the roadside. Life moves slowly out here, especially compared to the pace of the city. Kids often waved as I passed by, and I always made sure to wave back at them.

ne of the more unique experiences in Battambang is the bamboo train. Originally, the train tracks were built by the French for transporting goods, but after commercial use declined, locals repurposed the tracks. Rural communities started building makeshift “trains” from bamboo platforms mounted on axles and powered by small motors.

When they need to go in reverse or make way for another train, they simply lift the platform off the tracks and either turn it around or move it aside. These became an ingenious way for people in the countryside to travel, especially when roads were unreliable.

When Nicky, my tour guide, said it was the slow season, he wasn’t kidding. The bamboo train is usually one of the main highlights for tourists in Battambang. As a solo traveler, I was told I’d likely have to pay for two seats or wait and hope someone else showed up to split the cost. I ended up waiting for about 30 minutes, but no one came. I was ready to pay both, but decided to try negotiating for just one. Since it was so quiet, the vendor agreed to take me as a solo passenger.

Along the way, I saw small burns scattered across the countryside, with thin columns of smoke rising from piles of brush, rice husks, or harvested stalks. These controlled fires are common in rural Cambodia, especially around Battambang, where farmers burn agricultural waste to clear land or prepare fields for the next planting season. The air smelled faintly of smoke, and in some areas, a light haze hung over the fields.

On the return trip, a local girl asked if she could ride with me so she could meet her boyfriend somewhere down the line. I was totally cool with it. She laid her backpack and motorbike helmet on the platform and hopped on. Although I had booked the whole thing as a tourist, riding together made it feel less like a novelty and more like something ordinary, like a local commute.

We also stopped by Plov Thmey, a narrow suspension footbridge that stretches across a wide river. It’s mainly used by locals who ride motorbikes, cross on foot, or even drive their tuk-tuks across, often side by side. The whole structure sways and shifts slightly with each crossing. It definitely felt tight whenever a motorbike passed by me, but the locals seem to navigate it with ease.

While here, I met an older gentleman named Ho, who had been bicycling around the area. He was a fellow tourist, chatty and eager to connect. Born in Cambodia in 1955 to an ethnic Chinese family, he grew up speaking only Chinese. When the Khmer Rouge took over in 1975, he was 20 years old. He was sent to work in harsh labor camps, where he was forced to learn Khmer just to get by. “If not for the Khmer Rouge,” he told me, “I may never have learned Cambodian.” He paused for a moment, then added, “I was lucky. I survived.”

After years of cross-border attacks by the Khmer Rouge, Vietnam invaded Cambodia in late 1978 and quickly overthrew the regime, ending one of the most brutal chapters of the 20th century. In the chaos that followed, Ho’s family fled to Thailand, along with hundreds of thousands of others. But with refugee camps overwhelmed, they were forced to return to Cambodia. Eventually, after nearly a decade of uncertainty, they immigrated to Canada in 1987, where Ho still lives today.

Ho was full of stories. He was engaging, thoughtful, and often funny. The kind of person who could make you laugh one minute and reflect the next. He was also the first person I’ve ever met who had lived through the violent reign of the Khmer Rouge. When he visits Cambodia now, he chuckles at tour guides half his age trying to explain that era to him. “It’s kind of a joke,” he said. “They weren’t even born yet.” Hearing his firsthand account made that chapter of history feel far more real and personal than anything I’d ever read.

Roasted rats are a common sight along rural roads. We passed three or four vendors selling them as we drove through. Nicky told me he never suggests it as a stop for tourists because he knows most would find it unsavory. They tend to think of city rats, but these are actually rice paddy rats. In other words, they feed on grain and crops, not garbage like the ones you’d find in urban alleys. I’d seen them featured in videos before and was curious enough to give it a try, so I bought one.

I’ll be honest, the presentation left a lot to be desired. But taste-wise? It really did remind me of boiled chicken. I only had an arm and shoulder before handing the rest off to Nicky to finish off. It was too much for me to handle.

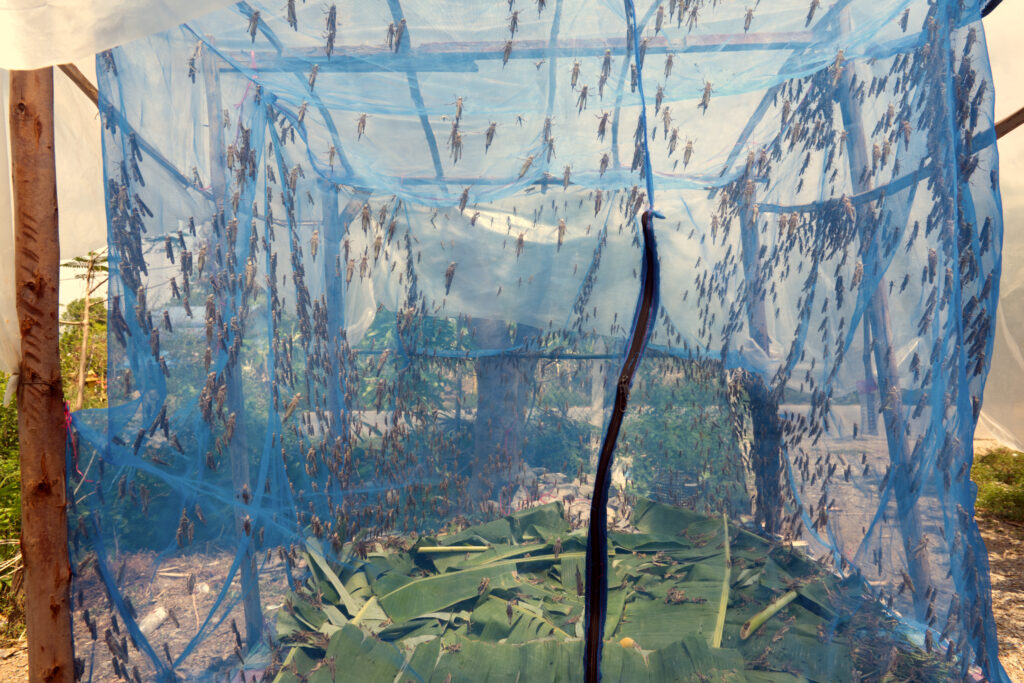

There are also tons of small-scale farming operations out here. For example, we stopped at a grasshopper farm right off the road. The family running it was kind enough to let me look around and take photos. For now, they just keep the grasshoppers in makeshift enclosures, feeding them until they’re large enough to sell. When they reach the right size, they fry them and sell them at roadside stands to passersby.

Banan Temple Hill was one of the two cultural landmarks on our itinerary. Often referred to as a “Mini Angkor Wat,” the temple sits atop a steep hill with more than 300 stone steps leading to the summit. The climb is a bit of a workout, but at the top, you come upon a quiet temple, its dark stone worn smooth by time and exposure. Despite its modest footprint, you can tell the temple played a significant role in the area at some point in its long history.

Many of the structures are in rough shape, with warning signs posted around crumbling walls and partially collapsed towers. It’s clear the site has endured centuries of wear and could benefit from some careful restoration. Still, it remains a peaceful and atmospheric place, a fitting introduction to Angkor Wat, which I’ll be visiting tomorrow.

The second historical landmark we visited was Phnom Sampov, a limestone mountain dotted with caves and pagodas. Carved directly into the cliffside is a colossal seated Buddha, its figure emerging from the rock as if the mountain itself had taken form.

It’s sadly best known for the Killing Cave, another haunting site reminiscent of the Killing Fields near Phnom Penh. During the Khmer Rouge era, victims were thrown or discarded into the cave, their bodies left to pile at the bottom. Definitely not a pretty image, but sadly, very on brand for the regime.

At the summit sits a golden pagoda complex, serene and peaceful. The buildings are modest but beautiful, with gleaming spires, colorful murals, and statues of the Buddha surrounded by offerings of incense and fruit. Monks still live and worship here, giving the site an active spiritual presence.

Sharing the grounds is a lively troop of monkeys, darting between visitors in search of food. They’re mischievous and bold, sometimes snatching snacks or offerings left unattended. Their constant movement adds an unpredictable energy to the otherwise tranquil setting.

From the edge of the peak, I took in sweeping views of the countryside, including rolling farmland, distant mountains, and the hazy outline of Battambang. I had hiked the full trail from the parking lot to the summit and back, passing on the motorbike ride that many visitors take as a shortcut up the hill. By the time I reached the bottom again, my legs were shaking and I was completely wiped out, but the effort made the experience all the more rewarding.

As a kind of finale, I stayed to watch millions of bats take flight at sunset. Just before dusk, they began pouring out of a narrow crevice in the mountainside in a continuous, swirling stream that lasted nearly an hour. They emerged in a tight, ribbon-like formation, twisting and sweeping across the sky as they began their nightly hunt for insects. It was an incredible sight, and a perfect way to cap off what had been a memorable tour.

Comments are closed.